Kodak discontinuing its High Speed Infrared Black and White negative film – known as Kodak HIE – was, in my humble opinion, a far greater loss to the film photography community than its false-colour positive Ektachrome Infrared – aka. Kodak EIR or ‘Aerochrome’.

The latter seems to get way more attention during this “second coming” of film photography, thanks in part to the vivid surrealist imagery of works by Richard Mosse (“Infra”) and Karim Sahai’s North Korean series, and more recently those by popular Youtube photographer Jason Kummerfeldt. The rest, I figure, is simply due to its unobtanium status, increasingly insane prices for the remaining stock and the simple fact that no other current film renders vaguely similar results.

Yet I’ll make the case that despite infrared black and white film still being made fresh today – namely in the form of Rollei IR400 and Ilford SFX200 – Kodak’s HIE was the more practical and less – dare I say it – ‘gimmicky’ emulsion. Known for its strong ‘wood effect’ landscapes, glowy foliage and deep, dark water and skies, many a landscape photographer mourns its passing.

Kodak HIE – or High Speed Infrared – was an infrared black and white negative film first introduced in 1937 and eventually discontinued 2007. As with Aerochrome, the scientific and industrial applications that had essentially underwritten production of the films for decades had all but disappeared when digital sensor resolution matched and then exceeded film by the mid-2000s. With Kodak haemorrhaging money and staring down an eventual bankruptcy, consolidation of film products was inevitable.

The magic of Kodak HIE, its differentiator from other competitors, lie in its extended infrared sensitivity. Whereas SFX200 is sensitive only a little into the IR spectrum, to around 720nm, and Rollei IR tops out around 750-760nm, HIE extends past 900nm, providing a much stronger infrared effect, even with a regular dark red (R25) filter. In contrast, both SFX200 and Rollei IR400 really need a full R72 filter to produce a noticeably ‘infrared’ look.

Kodak HIE’s other noticeable trait was its wild halations or ‘glow’ around highlights. This was thanks its thin polyester film base lacking an anti-halation layer. The result was a dreamy, ethereal quality to how highlights would render: not just the obvious IR-reflecting vegetation, but also as you’ll see below, on skin tones too.

Of course, I’d be remiss to not discuss Kodak HIE’s downsides, of which there plenty to note. Kodak wasn’t joking with the ‘high speed’ bit: the emulsion was very light sensitive and polyester base was notorious for light piping and fogging. The packaging made it plainly clear not to load or even open the film canister except in complete darkness. HIE was my first introduction to loading cameras in dark bags, and while the skill has served me well since (dealing with jams or reloads ripped out of the canister) I still remember being utterly terrified loading in my first roll, lest I poke the shutter.

Kodak HIE therefore, unsurprisingly, didn’t play well with cameras with film canister viewing windows either. Nor did it tolerate more modern cameras with IR sensors for frame spacing, which would duly fog the roll as it went. Thankfully my Nikon FM was suitably yesteryear for the film’s tastes, but it was still crazy to witness the light bouncing its way past the film gate.

It was also very grainy and at least in my experience, would render fairly soft images. Though perhaps my ahem, budget-conscious lens at the time was in part to blame.

Oh, and it was also quite expensive to buy back in the day, and required hand processing away from any machine or system with IR sensors or daylight loading. It hadn’t dawned on me some 25 years ago that developing my own films was even easier than darkroom printing (which I occasionally did), so the stuff around of finding a lab who’d do manually processing and the extra cost did limit my use of Kodak HIE.

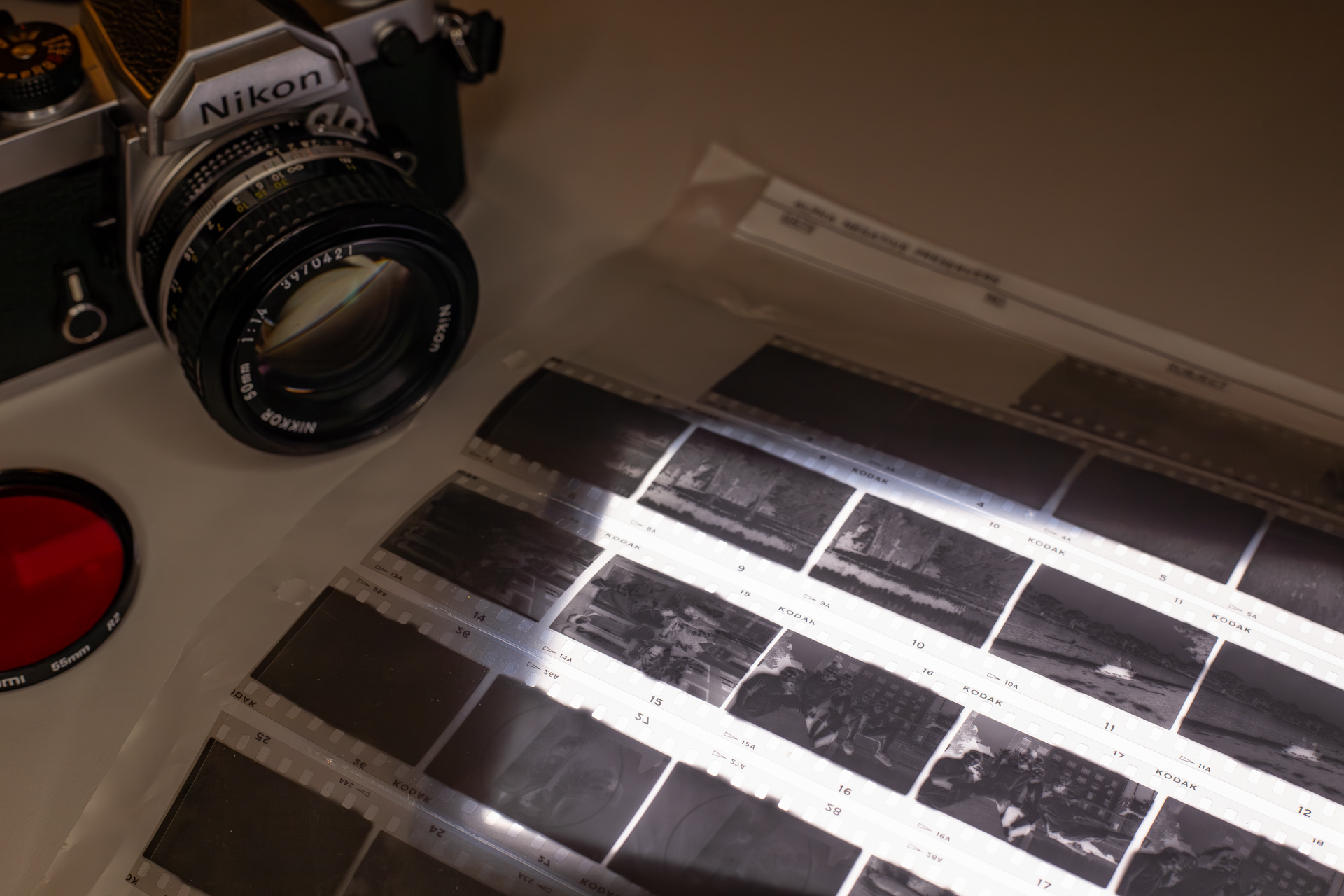

The following frames were shot back in late 2000, in and around Melbourne, Australia, using a Nikon FM – with either a Tamron 35mm f2.8 or Tokina AT-X 50-250mm f4-5.6 – and an R25 filter, generally shooting at between f8-16 to increase depth of field and try to minimise IR focus issues. I used the FM’s inbuilt meter and rated the film at 400 ISO: Kodak insisted HIE had no specific speed rating, that the ISO would be application specific, but most resources have stated ISO 400 works in most applications.

Film was scanned on a DSLR rig, consisting of a Canon 6D, Nikon PB-6 bellows, Schneider-Kreuznach Companion-S 100mm enlarging lens, CineStill CS-Lite and a 3D printed film guide/mask. RAW scans were inverted in Lightroom Classic and adjusted for contrast and balance.

The classic black and white infrared shot. Glowy tree foliage, black water and dark(ish) skies. Also lots of grain and not a tonne of detail. I still have a silver gelatin print of this image – one of the first I’d ever made – hanging in my dining room.

The classic black and white infrared shot. Glowy tree foliage, black water and dark(ish) skies. Also lots of grain and not a tonne of detail. I still have a silver gelatin print of this image – one of the first I’d ever made – hanging in my dining room.

This portrait of my then-neighbour Chris demonstrates how pleasing skin tones could render. Old mate was a handsome fellow, for sure, but the film is definitely doing some softening of fine detail, resulting in what I felt was a quite the flattering portrait.

This is was a cancer awareness art installation installed in a local park that a friend and I visited to photograph, his daughters walking through the rows of what must of been hundreds if not thousands of cut out cardboard hands, each representing (if I’m remembering correctly) a lost loved one from the disease. Quite the poignant scene. Of note is how the many different colours and tones of the hands have been essentially lost by the red-filtered IR emulsion, mostly turned towards white in the midday sun.

This is was a cancer awareness art installation installed in a local park that a friend and I visited to photograph, his daughters walking through the rows of what must of been hundreds if not thousands of cut out cardboard hands, each representing (if I’m remembering correctly) a lost loved one from the disease. Quite the poignant scene. Of note is how the many different colours and tones of the hands have been essentially lost by the red-filtered IR emulsion, mostly turned towards white in the midday sun.

This image of Melbourne’s skyline poking over the trees highlights the difference in how infrared film renders natural foliage versus hard concrete and glass.

I wish I could recall more rationale for this experiment (hey, it was 25 years ago!). I think I was curious what amount of IR light a candle would emit. Answer – not much. The halo-ring flare was quite odd and the double-exposure leans into the ethearal, ghostly quality of Kodak HIE generally.

Of course, Kodak HIE is long gone and – by all accounts – is very unlikely to ever come back. Whether or not consumer demand could ever justify redeveloping old emulsions to meet current environmental regulations, Kodak’s film coating and handling lines were upgraded in 2011 with numerous IR sensors for quality control purposes to boost yield. This is just an educated guess – please if you work for Kodak, let me know otherwise – but I suspect those same sensors would likely interfere with an extended IR range emulsion like HIE or EIR. Given how seemingly fraught the economics of current regular colour film production are, new specialty infrared film seems a wish too far.

Old expired rolls of Kodak HIE are still somewhat available on eBay and the like – at a hefty price. However, the results I’ve seen from recently shot expired HIE aren’t encouraging. The emulsion does not appear to age well at all, with fogging, lack of contrast and other artefacts common. Unless you’re sure the film has been kept frozen since the first decade of the new millenia, it’s probably not worth forking over serious money to try – unless you’re desperate.

Which is a darn shame, because Kodak HIE was a wild beast. But, unlike its colour brother, modern day alternatives still (kinda) exist.

Share this post:

Comments

No comments found